The best temperature to brew coffee

The best brew temperature for your coffee should be between 85-95 degrees Celsius (°C) / 185-203 degrees Fahrenheit (°F) — slightly less than the boiling point of water.

Table of contents

For specific brew methods we recommend these temperatures:

- Aeropress:

90-95°C / 194-203°F - French press / cafetière:

90°C / 194°F - Steep-and-release:

93°C / 199°F - V60:

91°C / 196°F - Chemex:

94°C / 201°F - Pour-over:

90-93°C / 194-199°F - Espresso:

92°C / 198°F

Read on to find more detailed recommendations for your brew method.

How water temperature makes a difference

The hotter the water, the faster and more effective it will be at extracting flavour from your coffee. This is most evident when contrasting brew methods like pour-over and cold brew. Pour-over uses near-boiling water takes a few minutes to brew, while cold brew can take over a day to complete.

The brew time is determined by the speed at which the compounds in coffee dissolve. The higher the temperature of the water, the faster they dissolve.

Compounds that are harder to dissolve (often undesirable ones that make a less tasty brew) are more likely to be extracted the hotter the water. This is why many prefer to use water below boiling point to avoid extracting unwanted flavours.

It's for this reason that you should pick a specific water temperature. It can define the length of brew time, and can give you more control over which solubles are extracted and at what amounts.

There are more effective variables in coffee brewing that control these same factors — like brew ratio, grind size, and dose — but if you're changing these variables and still getting bad results, you should consider changing your water temperature.

Temperature isn't something you should have to control excessively. If you've found a good temperature that you can repeat consistently in your brewing process, you'll be fine. Fellow Stagg EKG Electric Kettle *If you make a purchase through these affiliate links, we may earn a commission at no extra cost to you.

Slurry temperature vs. water temperature

The most important temperature to monitor in any brew method is the coffee water mixture (or slurry) — this is the temperature of the extraction process. Knowing this temperature is essential to understanding the correlation between the chemical processes in your brew and the taste of your coffee.

If you record the temperature of a coffee water mixture that makes a good tasting cup, you can replicate the same temperature in another brew, or even a different brew method.

But because water cools quickly, the temperature indicated on a kettle or an espresso machine will not be the temperature of your coffee water mixture. Even if you pre-heat your brewer or grounds, the brew temperature can drop 10-15°C / 18-27°F.

If you want the slurry to be at 93°C, you have to heat the water at a higher temperature, potentially at boiling point.

Most temperatures recommended on guides and recipes are temperatures of water before contact with coffee, not the brew mixture. The rate of cooling varies, as it is affected by factors like room temperature and material of the brewer. This means your slurry temperature will not alway be the same as someone else's — even if you followed the same recipe.

If you're able to brew coffee consistently, the slurry temperature shouldn't matter at all. Problems arise when sharing temperature recommendations — they may not have the same environment or processes as you and won't be able to achieve the same results.

If you've made a good brew, make sure to record the temperature of the brew mixture with a cooking thermometer when you next make it. Then you know how you can achieve that brew temperature with that specific starting water temperature and brewing process. This brew can be recreated by others and their methods, so long as they hit the same slurry temperature using a thermometer.

For most brewers (even espresso), it isn't realistic to have the brew temperature remain at over 95°C / 203°F. Water cannot stay that hot without constant reheating, even with pre-heated equipment.

Boiling water

There are many sources that claim that boiling water should not be used when brewing coffee. Over-extraction, risk of burning the coffee and shorter brewing times are some of the disadvantages given to this statement.

However, there are many circumstances where the use of boiling water is reasonable or even preferred. Keep on reading to find when the use of boiling water may be appropriate.

How to decide on a temperature

You should decide your water temperature after you consider these factors:

- Coffee roast level

- Brew method

- Level of cooling

- Tasting

Coffee roast level

The more coffee is roasted the more porous it becomes, with darker roasted coffees becoming easier to extract flavours from. Therefore, it is recommended that lighter roasted coffees be brewed at higher temperatures than darker roasts.

We recommend a these temperatures for different roast levels:

- Light roast:

90-96°C / 194-205°F - Medium roast:

87-95°C / 188-203°F - Dark roast:

82-93°Cor178-200°F

Note. These are the temperatures for the water coffee mixture (slurry), not water temperature before pouring.

Brew method

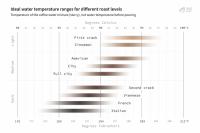

Depending on your choice of brew method, you should consider setting your water temperature within these ranges.

For immersion brew methods

For immersion brew methods we recommend these temperatures:

- Aeropress:

90-95°C / 194-203°F - French press/cafetière:

90°C / 194°F - Steep-and-release:

93°C / 199°F

These methods retain a higher temperature for much longer than percolation methods, as they retain all the water when brewing. If you're using water off the boil, the water should drop to around 89-93°C / 192-199°F. Using boiling water is fine, but if it tastes over-extracted try lowering it by 2-3°C / 4-6°F.

When dialling-in, make changes no less than 1°C / 2°F , as changes less than this will make no perceivable differences in taste. You can make changes of up to 3°C / 5.5°F.

For percolation brew methods

For percolation brew methods we recommend these temperatures:

- V60:

91°C / 196°F - Chemex:

94°C / 201°F - Other pour-over:

90-93°C / 194-199°F

Percolation brew methods lose heat much faster than others. This is because water is constantly lost from the mixture while brewing, taking longer to heat up. The temperature in the slurry often below 75°C / 167°F to start with and then gradually rising to around 90°C / 194°F.

If this temperature is good for you, it is perfectly fine to use boiling water.

These methods are less consistent in temperature as they calculate depending on the flow of water, pulsing and changing water temperature. When taking the slurry temperature, you will find that it fluctuates drastically, resulting in an unclear reading. What we would say it to use the highest temperature reading as your result.

Stove/hob based brewers

These methods give very little control of temperature. The strength of the flame or heater can be altered but the water will always hit boiling point regardless. We recommend a low-medium heat, as this will increase brew time.

For stove-top coffee makers, adding boiled water into the lower chamber will reduce the amount of time the grounds are hot, which may decrease bitterness.

For Turkish coffee, aim to stop the heat just before it look like it will boil, then let it simmer. This will reduce over-extraction.

Here are our recommendations for stove top brew methods:

- Moka pot:

low-medium heat - Vacuum coffee maker / siphon:

low-medium heat - Turkish coffee:

just below boiling

For espresso

The water coffee mixture is much hotter in espresso as the basket is heated to a very high temperature. If you can set the temperature on your espresso machine, we recommend setting it around 92°C / 198°F.

When dialling in, make increments in temperature of at least 1-2°C / 2-4°F, and see how it tastes. Avoid making smaller changes than this (like 0.4 degrees) as it won't make a perceivable enough difference in taste.

Level of cooling

Depending on the brew method you use and the material the brewer, the rate of cooling can greatly differ. In pour-over cones for example, porcelain, glass and resin cones retain heat for much longer the metal ones, and bigger cones with larger surface area will lose heat faster.

This is where a thermometer would be useful. Use thermometers to take readings while brewing to see how much the temperature drops by to know the cooling rate of your brew method and process.

Pre-heating your brewer can help decelerate the cooling of your slurry temperature by a few degrees. Add boiling water to your brewer (be it an Aeropress, V60, or a cafetière), leave the water while you do a different task, then empty it carefully before you start brewing.

Tasting

The previous factors rely on measurable principles but tasting is subjective. Ultimately, you should decide on a brew temperature that makes the best tasting coffee to you.

- If it tastes over-extracted, reduce the temperature

- If it tastes under-extracted, raise the temperature

Temperature isn't the most important variable in the brewing process. Once you've settled on a temperature — you shouldn't have to worry about it. However, it makes a small difference — enough to get nerdy about it.

There are recipes that play around with water temperature, like Tetsu Kasuya's hybrid recipe for the Hario Switch, which uses drastically lower temperatures to slow the rate of extraction. Check out his videos to find more about using different temperatures.